Automatic Programming 2.0

13 Aug 2025 - Lorentz Vedeler

Before 1954 almost all programming was done in machine language or assembly language. Programmers rightly regarded their work as a complex, creative art that required human inventiveness to produce an efficient program. Much of their effort was devoted to overcoming the difficulties created by the computers of that era: the lack of index registers, the lack of built-in floating point operations, restricted instruction sets (which might have AND but not OR, for example), and primitive input-output arrangements.

– Backus, 1978 1

IBM introduced FORTRAN, short for Formula Translating System, in 1956. Only a few years behind Autocode, it was one of the first compiled languages and arguably the first really popular compiled language. Compilers represented a paradigm shift in computer programming.

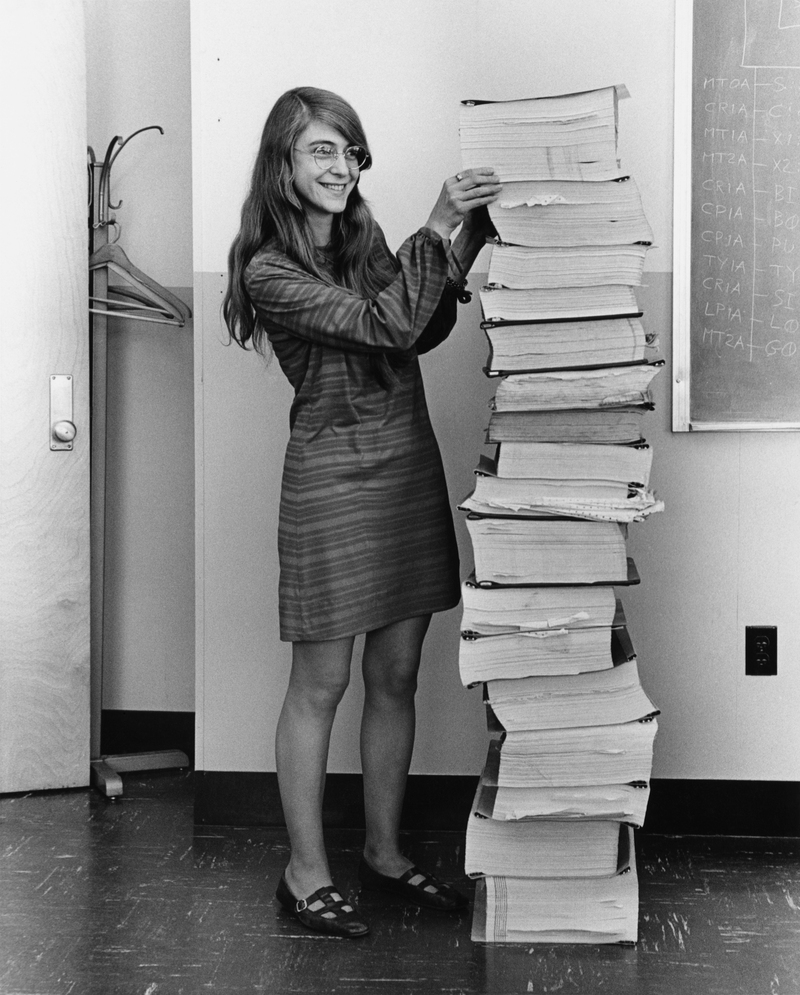

Before compilers such as FORTRAN, programmers would write assembly mnemonics on paper. A keypunch operator would use a keypunch machine to write the assembly to a stack of punched cards. These cards would then need to be assembled into binary op codes with an assembler program. If you wanted to proof-read your punched cards, you could add a card with instructions to list the rest of the stack of cards; the computer would print the program source back to you. You may have seen the picture of Margaret Hamilton with the listing of the source code for the Apollo guidance software before.

Programming with punched cards was tedious, if you wanted to make a correction to a program, you would have to punch out a new card with the corrections made. With absolute addressing, that might involve jumping to a previously unused address so that you could make the correcting instructions and then jump back.

In fact the programming workflow of the early 1950s was so complicated that I am unsure I can even understand all the work it took to run a program, I may have left out a few details. Even in 1978, Backus says it is hard to comprehend how drastically workflows have changed since then. Being born more than 20 years later than that again, I hope I am excused if I get some details wrong.

It is difficult for a programmer of today to comprehend what “automatic programming” meant to programmers in 1954. To many it then meant simply providing mnemonic opera- tion codes and symbolic addresses, to others it meant the simple process of obtaining sub- routines from a library and inserting the addresses of operands into each subroutine. Most “automatic programming” systems were either assembly programs, or subroutine-fixing programs, or, most popularly, interpretive systems to provide floating point and indexing operations.

– Backus, 1978 1

Given how laborious the programming process would have been in the fifties, you would expect automatic programming to be adopted by everyone. But as Richard Hamming writes in the book “The Art of Doing Science and Engineering”, programmers at the time were not exactly enthused by automatic programming:

FORTRAN […] was opposed by almost all programmers. First it was said that it could not be done. Second, if it could be done, it would be too wasteful of machine time and capacity. Third, even if it did work, no respectable programmer would use it — it was only for sissies!

Now there were legitimate criticism against FORTRAN. As it basically runs a virtual machine to enable floating point operations, it was slower than manual assembly programs written by expert programmers. It did however go on to be a massive success in the end. Some FORTRAN systems are still in production, 70 years after its release — a monumental achievement. Still Backus is not quite as happy as you would think. In 1978, Backus mentions that programmers clinging to FORTRAN and other similar languages hinders adoption of new even more innovative languages:

My point is this: while it was perhaps natural and inevitable that languages like FORTRAN and its successors should have developed out of the concept of the von Neumann computer as they did, the fact that such languages have dominated our thinking for twenty years is unfortunate. It is unfortunate because their long-standing familiarity will make it hard for us to understand and adopt new programming styles which one day will offer far greater intellectual and computational power.

– Backus, 1978 1

In 2025, this may sound familiar. LLMs such as Anthropics Claude and Open AIs GPTs are set out to perhaps reach the final stage of automatic programming. As a sort of non-deterministic compiler for plain english (or any language you are fluent in).

Throughout my career in computing I have heard people claim that the solution to the software problem is automatic programming. All that one has to do is write the specifications for the software, and the computer will find a program.

…

In short, automatic programming always has been a euphemism for programming with a higher-level language than was then available to the programmer. Research in automatic programming is simply research in the implementation of higher-level programming languages.

– Parnas, 1985 3

In 2025 it is entirely possible to write the specifications for a program and let the computer “find a program”. Now we do not call it automatic programming, but “vibe coding”. Again many programmers remain skeptical. And again there are many legitimate criticisms of the current coding agents and tools. Experts still write better software than LLMs will produce. For now at least.

In the recently published Stack Overflow devloper survey, as many as 66% of programmers responded that their biggest grievance with AI tooling was that it would generate code that was almost correct, but not 100 %. When I answered the survey, I was in that group. I am not any more. The improving in tooling over the last year are astonishing. It is certainly not perfect, and I assume we cannot extrapolate this rate of improvement for much longer, but I suspect that english as a programming language will only increase in popularity going forward.

I also believe dismissing LLMs is a mistake. There are still programs written in assembly today, but not nearly as many as were written in the 1950s. There are many projects that do not require very sophisticated programming, and that did not make economic sense before LLMs that may now be possible. A few years ago, such problems would be solved with low-code or no-code solutions. The problem with such solutions is that they are pretty much impossible to hand-over to “real” programmers if they outgrow their platforms. I expect LLMs will raise the bar for complexity required before the “real” programmers get called in, with the advantage that the output of an LLM is the same as a programmer, albeit with perhaps slightly worse quality. LLMs can be instructed to follow good development practices, such as adding tests etc.

If you think of LLMs as a non-deterministic compiler, it is hard not to see the echoes of the 1950s in the AI skepticism today, an I think you can expect LLMs/AI to be at least as impactful on our profession as the compiler has been before.